On the surface, DevOps is just another buzzword, i.e. something a lot of people talk about without fully understanding or doing it.

Stats have been floating around about the benefits of DevOps to organisations big and small. It seems so widespread that you almost feel FOMO. Some examples include (ranging from hype-like growth to more “modest” depiction):

- DevOps adoption is expected to reach 93% by the end of 2015 (Rackspace, 2014)

- DevOps adoption grew from 66% in 2015 to 74% in 2016 (RightScale, 2016)

- By 2016, DevOps will evolve from a niche strategy employed by large cloud providers to a mainstream strategy employed by 25% of Global 2000 organizations (Gartner, 2015)

- DevOps teams increased from 16% in 2014 to 27% in 2017 (Puppet, 2017)

Along with DevOps, Docker as a tool for containerisation is quickly becoming a hot name. Before we get into how containerisation fits in DevOps, I’d like to emphasise a couple of important points:

- Using Docker doesn’t mean you’re “doing” DevOps

- DevOps doesn’t mean using containerisation or Docker

What’s DevOps anyway?

Ever heard of the “Blind men and an elephant” parable? Having never come across an elephant before, a group of blind men tries to conceptualise what the creature is by touching it. Each blind man feels a different body part of the elephant, and comes up with a different description for the animal.

The blind men and an elephant. Source: Wild Equus

The blind men and an elephant. Source: Wild Equus

The same could apply to DevOps’ definition. It is probably the combination of all the things you commonly hear associated with DevOps.

As mentioned before, DevOps is not tied to a particular type of technology (e.g. containerisation) or particular toolkit/frameworks in software development.

Most technology vendors talk about some aspects of DevOps. For instance, Amazon talks about it in terms of philosophy, practices and tools. Atlassian discusses it as “a culture, a movement, a philosophy.” Google calls it “Site Reliability Engineering.”

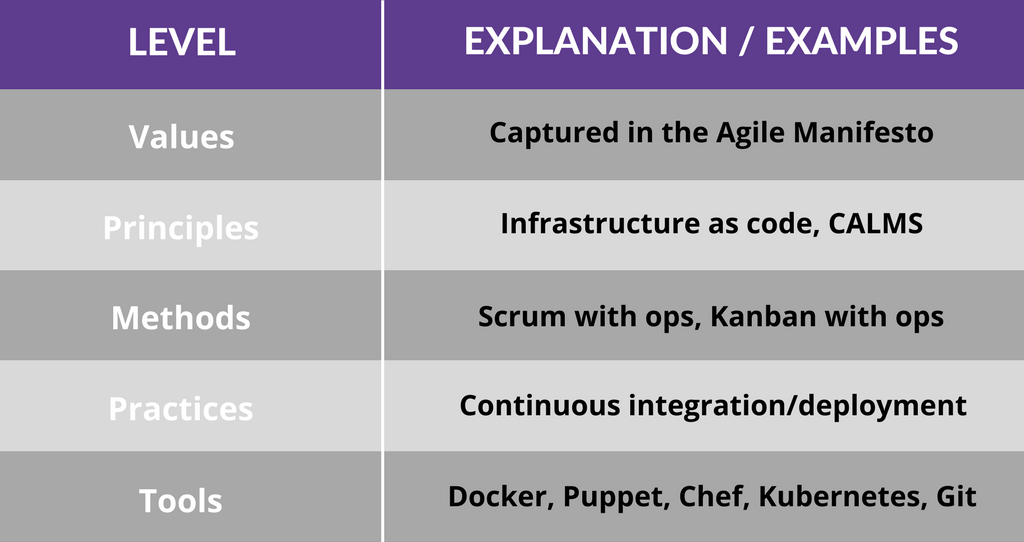

One of the most comprehensive definitions I’ve come across looks at DevOps as a five-level structure. Also worth noting is DevOps’ close linkage with Agile and Lean approaches.

It’s fundamentally about bringing agile software development practices and automation to the world of IT and Service Operations.

DevOps’ definition in depth. Based on: The Agile Admin, AWS, Atlassian

DevOps’ definition in depth. Based on: The Agile Admin, AWS, Atlassian

This article zooms in containerisation (containers) at the “Practices” level, and then Docker among others at the “Tools” level.

Containers: definition and benefits

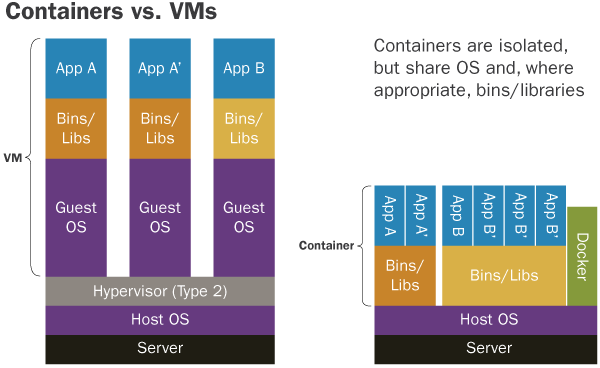

Containers are a collection of technologies that allow server applications to be built, packaged and deployed as an isolated, atomic unit - reducing the risk of dependency mismatch, getting servers into unknown configurations, and reducing the potential effect intruders can have from compromised services.

Containers allow server applications to be self-contained and replicated across different developer machines.

Conceptually, they are similar to Virtual Machines which have long been used to replicate servers across different machines and to isolate different applications from one another, but containers are more lightweight and Docker provides a better development experience than the Virtual Machine alternatives.

Source: SEI Insights

Source: SEI Insights

Projects like Eclipse Che are promising - they use Docker containers to allow users to share development environments via the web, and recreate the exact environment of another developer when investigating bug reports.

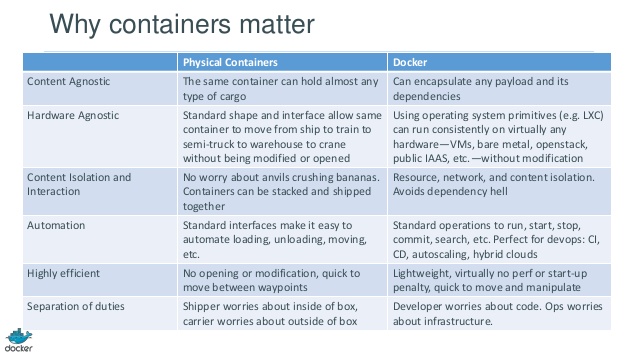

How containers like Docker work can best be understood using the analogy with physical shipping containers, as shown in the image below.

Source: dotCloud

Source: dotCloud

How containers fit in with DevOps

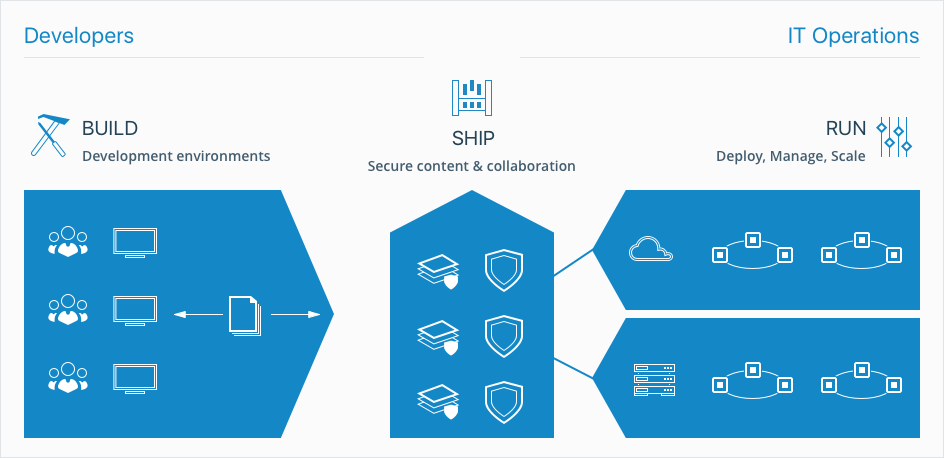

Traditionally, there’s been some tension caused by the Dev-Ops silos, with Devs wanting change and Ops wanting stability. Containers serve as the mediator, providing benefits to both sides while allowing each to do what they do best.

Source: Docker

Source: Docker

For instance, containers help improve the quality of code produced by developers, which makes Devs happy. Or containers improves reliability of continuous integration systems, which makes Ops happy.

Atlassian’s DevOps-style software development cycle puts containers in the Build phase.

Source: Atlassian

Source: Atlassian

From another perspective, this periodic table of DevOps tools doesn’t lay out how the different steps link to each other like above, but provides a fairly comprehensive overview.

What options are there for containers?

The rate of container adoption ranges from 26% (but if you include those “experimenting” as well, the rate goes up to 62% - RightScale, 2016) to 79% (ClusterHQ, 2016)

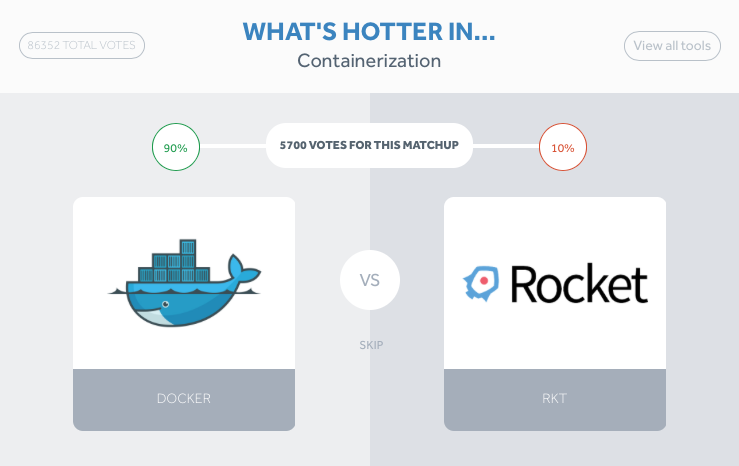

Docker is the big player in the container space with Rocket being the only major competitor. There are some proprietary solutions emerging, but Docker is actually a combination of a specific technology and a standard way of building and interacting with containers, so most of these technologies are compatible with each other through the Open Containers Initiative (OCI).

Seeing as the core technologies behind Docker are open-source and free, there isn’t a large incentive for competition in the container space.

Apart from stats elsewhere, results from this interactive poll on DevOps tools present a pretty concrete case for Docker’s dominance in containerisation.

Source: XebiaLabs

Source: XebiaLabs

There is a lot more competition in the Container Orchestration space. This is software that manages the servers and ensures that the Docker containers are running as specified.

The main players here are Docker Swarm (created by Docker) and Kubernetes (also open-source, but mostly created by Google).

Google offers a hosted Kubernetes service as part of their Cloud services. Amazon AWS has Elastic Container Service for their Cloud but it lacks much of the functionality from the other services. Mesos/DCOS is another large player but is mostly focused on users running their own data centers.

Service orchestration is a paradigm shift in how services are deployed and managed that is cloud native. Traditional methods of managing services using Enterprise Service Buses (ESBs) are hard to scale and provide single points of failure.

Kubernetes and its alternatives came out of Google’s hard earned knowledge on how to scale services to be global scale through tool automation. This investment in automation also has the benefit of making small services cheaper to set up.

Container is a relatively new technology, so the orchestration landscape is still shifting with no clear winners at the moment.

What to look for when choosing a container solution

Docker is going to be the only real choice for the container engine itself.

For container orchestration, this really depends on the specific use case. Here are some brief reviews of each option:

Docker Swarm is included with Docker and has a very small setup cost. It doesn’t have the level of engineering effort and configurability as Kubernetes. It’s great if you just want to get started with an out-of-the-box solution, but it may require additional infrastructure setup for large scale deployments.

Mesos DCOS is only really needed if you have a fleet of servers that you want to monitor and manage that can’t be managed via Cloud services. This is good for enterprise on-premise data centres. This is a bit lower level than the other options, and in fact you can run Kubernetes on top of DCOS/Mesos if preferred.

AWS ECS is okay if you need a basic orchestration system on AWS that integrates easily with other AWS services like EC2 and ELB. The downside: it generally is not kept up to date with the latest versions of Docker and is somewhat opaque for debugging purposes.

Kubernetes is more complex but it provides the most configuration and flexibility. There is a hosted service by Google that integrates seamlessly with their cloud solution. However, being open-source, there are engines for Kubernetes to deploy your Containers to AWS, Azure or other cloud providers.

This gives you the ability to create cross-cloud infrastructure for redundancy or to move away from Google if required, unlike ECS. The up-front investment is high, but it is the best option for large scale services.

What are the best practices to secure containers?

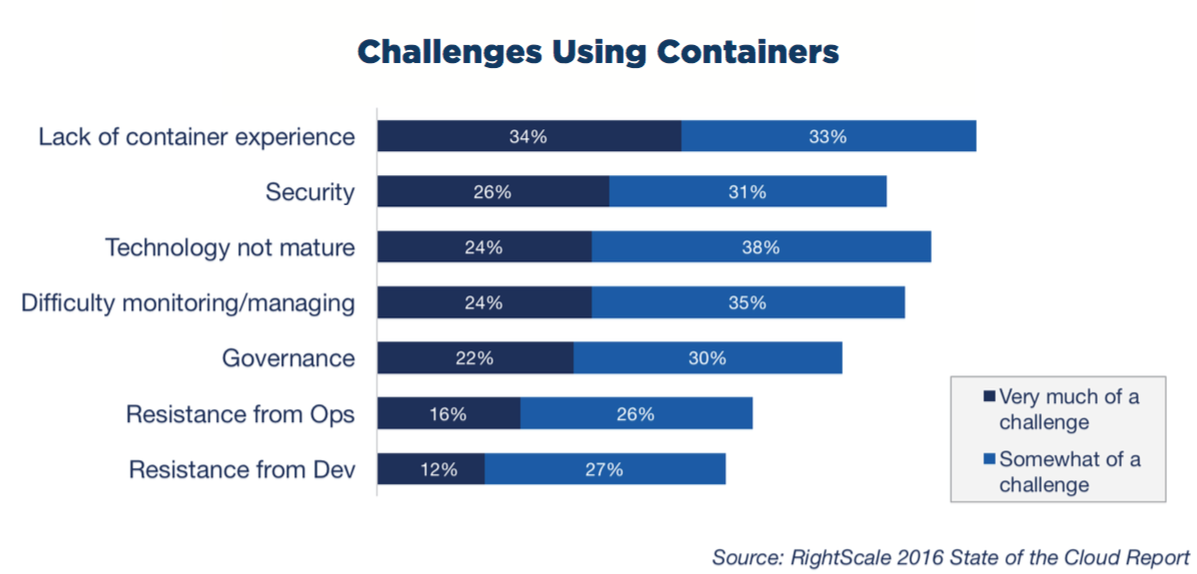

Containers are not generally considered secure by default. Unlike virtualisation technology, it does not rely on the hypervisor to provide physical security between the processes. That said, some basic things can be done to help ensure that the containers have been secured to the best effort.

Security as one of the top challenges. Source: RightScale

Security as one of the top challenges. Source: RightScale

Don’t expose Docker’s socket to the container if the container has ports exposed to the internet

Docker uses a HTTP socket for clients to control it - this socket allows commands to be run on the server as root (Docker must run as root). Normally, a container cannot access this socket internally, but sometimes automation tools require access to it so they can control the Docker instance. These tools should not also be accessible from the internet.

Don’t allow untrusted code to run in a container

Docker is not ideal as a platform for running user created code as there may be escalation exploits in the OS Kernel that let containerised code escape the container and run on the host system unimpeded.

Hosts like hyper.sh run containers directly on the Hypervisor and thus get the benefits of both Virtual Machines and Containers. This could be an option for a hosting solution for multi-tenant services.

Ensure that you are only building from trusted Docker images in your Dockerfile

Only use verified images as your base images. If you use a third-party image instead, and that user’s account is compromised, attackers can update their image to inject compromised binaries which your next build will then use. This could give them access to your services and databases.