Would you care if the brands you interact with everyday disappeared? A global survey says nearly three-quarters of those asked wouldn’t care. Would what we do as marketers, branding strategists, advertisers or product managers matter anymore? But before it turns into a philosophical debate about the meaning of existence, let’s quickly return to reality.

Not long ago, I attended a thought provoking event by Brand South Australia discussing the future of brands and how the “Future Enterprise” can foster trust in consumers.

It comes down to a very simple idea that sometimes clashes with capitalism. It’s about social good. This has led me to step back and look at the big picture of brands.

Trends that may decrease significance of brands

A problem for some

With the advancements in digital technologies and decline in broadcast media, brand marketing has become harder.

In a previous post on customer experience, we’ve said consumers are more demanding and hold more power. It’s no longer a one-way street where brands broadcast their messages to customers.

Tech-savvy millennials can now talk back and demand transparency, thanks mostly to social media, which means they can affect brands positively or negatively.

Even with sophisticated ad targeting technologies, they are tuning out of brand advertising, with the rise of ad blockers.

An advantage for others

While there has been a proliferation of startups, the concentration of brands is also happening at a staggering rate.

They got “swallowed up” by large corporations, namely “GAFA” (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon).

These giants are the aggregators, sucking brand affinity from other companies by taking care of the distribution.

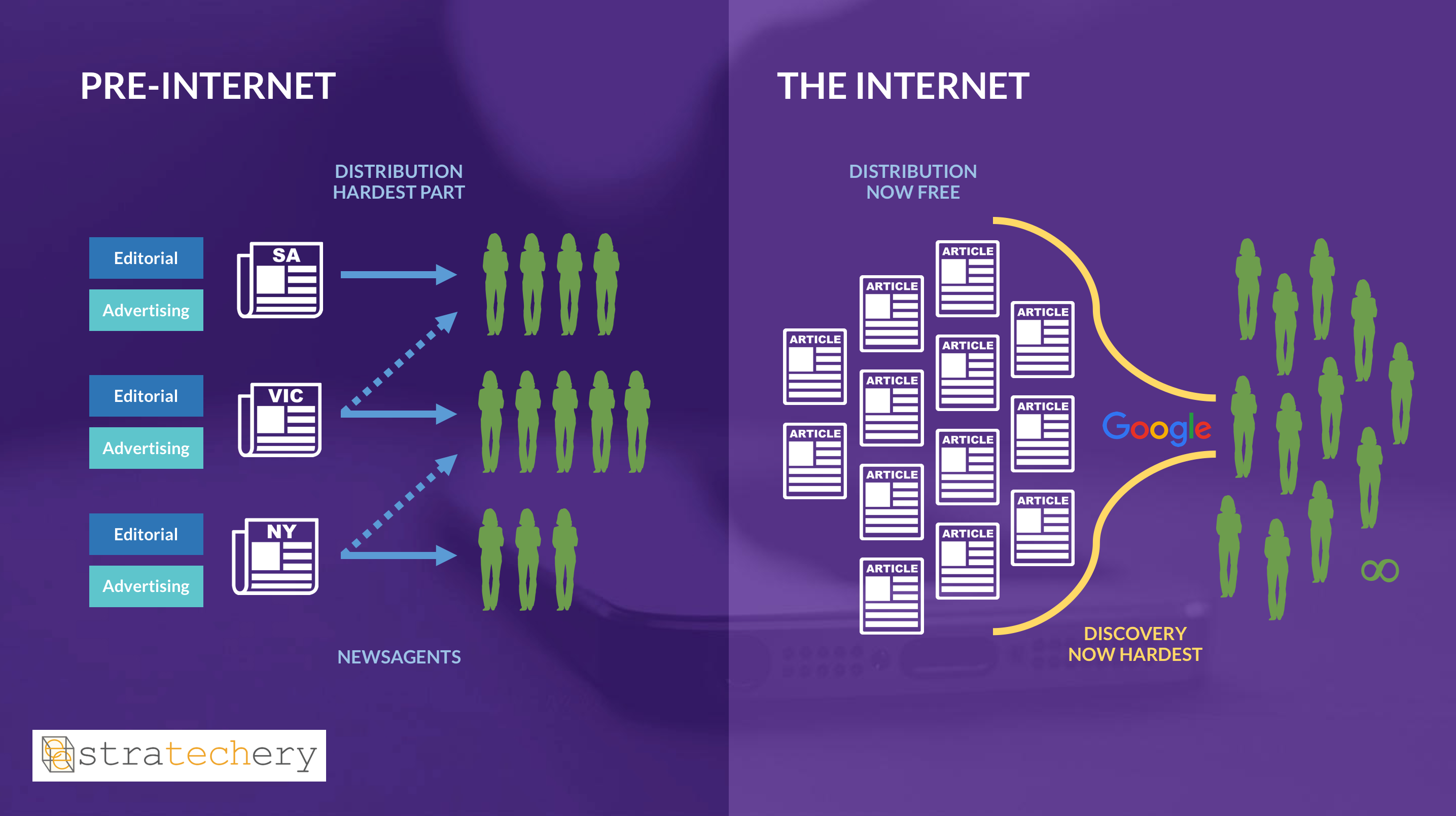

Think about how Google aggregates content from all sources. Think about how Amazon aggregates suppliers of books, then all sorts of consumer goods. This is the Aggregation Theory at work.

How Google “dilutes” the brands of publishers and media companies. Based on Ben Thompson’s Aggregation Theory

How Google “dilutes” the brands of publishers and media companies. Based on Ben Thompson’s Aggregation Theory

Millennials value convenience, experience and access.

Here’s a hypothetical situation that may well be true soon. With voice commerce and smart speakers like Amazon’s Echo, consumers may delegate the choice of brands to AI algorithms.

For example, “Alexa, buy the cheapest toothpaste,” or “Hey Siri, order some detergent, whatever that gets here the fastest.” So brands may not matter as much as price.

More current stats include consumers wouldn’t care if 74% of the brands they use just disappeared. In the US, a third of those surveyed wouldn’t care if Twitter disappeared. In Australia, “95% of brands could disappear and Australians wouldn’t care.”

So that brings us to the question: “What would make consumers care?”

Trends that may increase the importance of socially conscious brands

Like most humans, consumers want to be heard, appreciated and advocated for. They want to be able to trust that organisations are doing their best to make their lives better.

The Guardian has a thought-provoking article on how technology disrupted the truth. With the prevalence of fake news, alternative facts and such, the default for this generation has become “not trusting.”

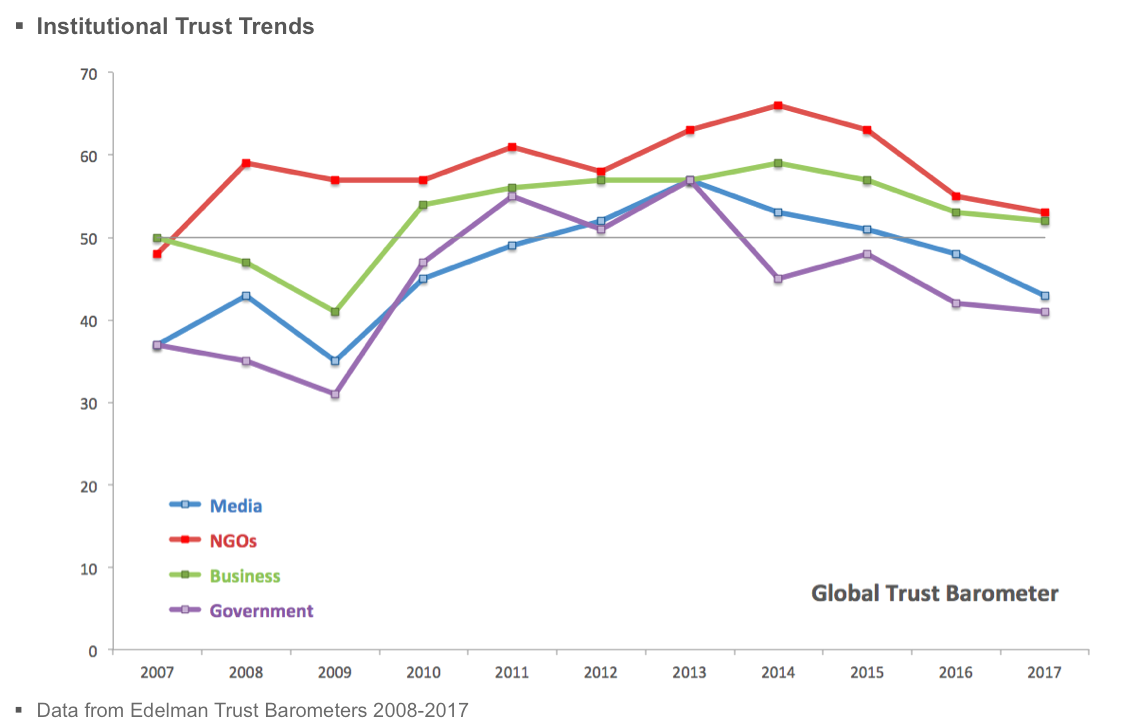

In fact, trust in traditional institutions is falling, particularly in the government. NGOs and businesses are the only two that hover above the 50% public approval levels.

Check out the graph below based on the Edelman Trust Barometer – which has been tracking global trust in institutions for the past 15 years.

Source: True Economics

Source: True Economics

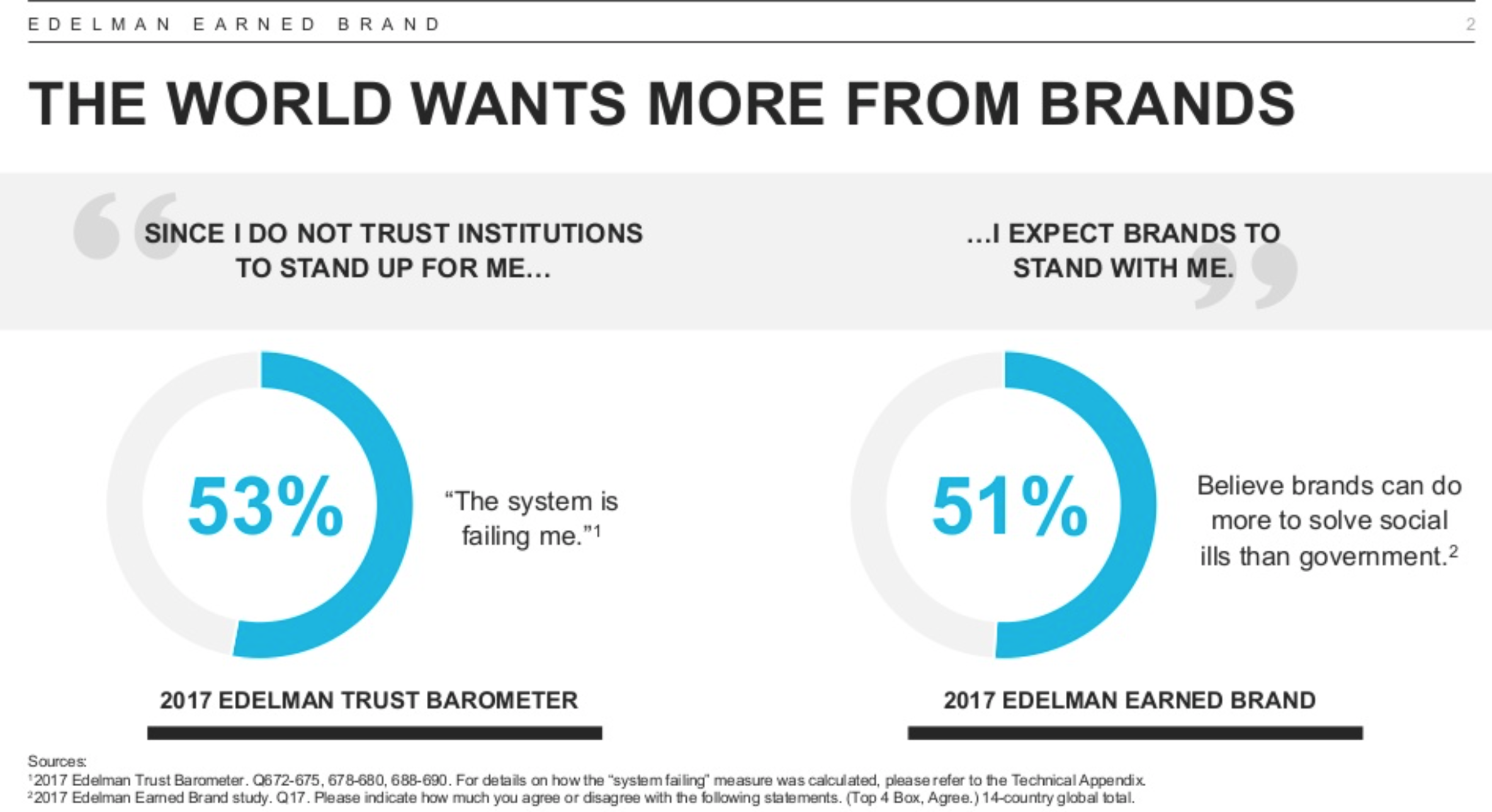

Does this mean good news for businesses? Not quite. Because consumers are expecting more.

Source: Edelman

Source: Edelman

Or this stat:

Source: Havas Group

Source: Havas Group

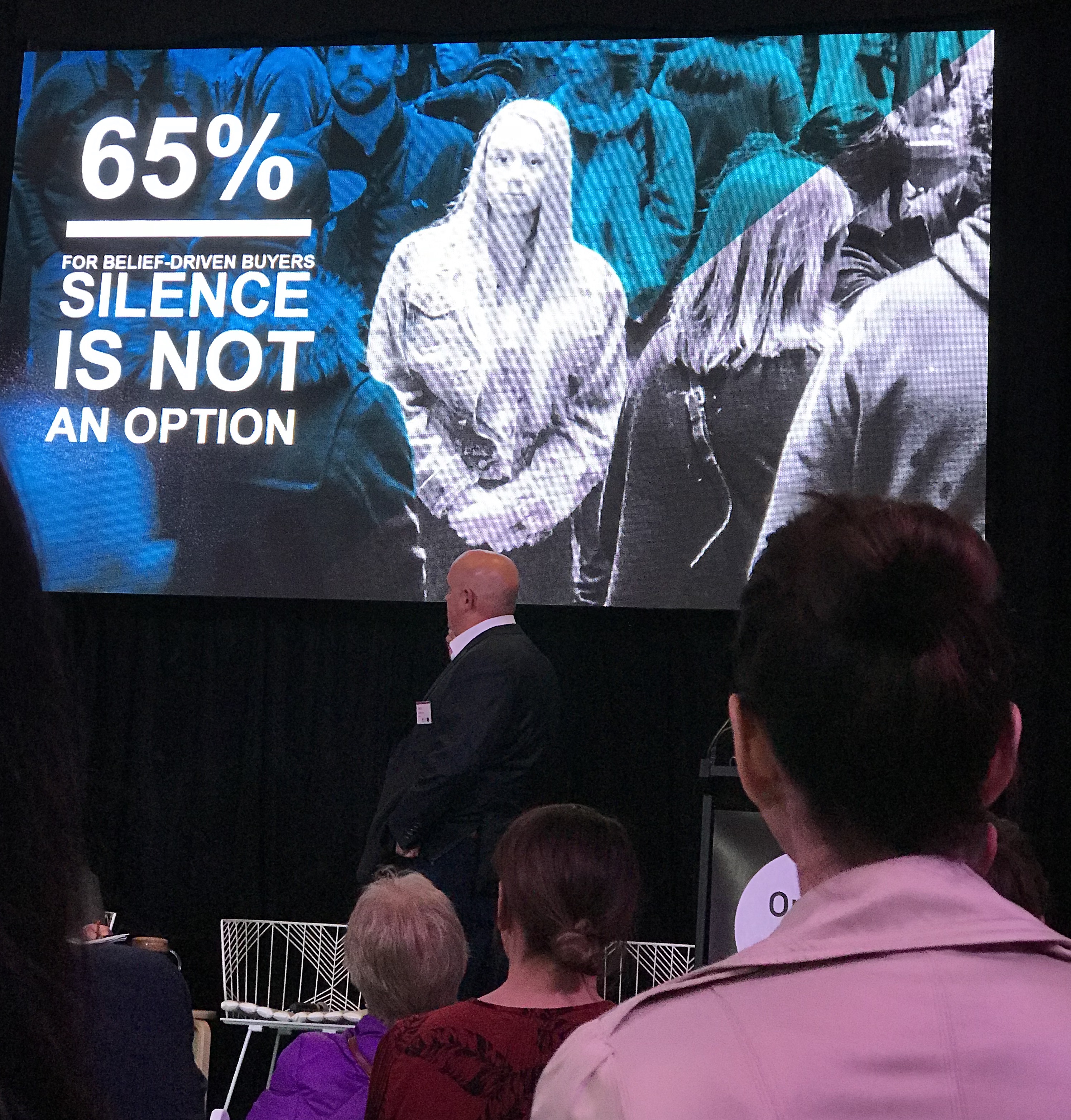

Cue the rise of belief-driven consumers. Some more stats from the Edelman studies:

- 50% of buyers now buy on belief

- 81% believe that business can pursue its self-interest while doing good work for society

Who are these consumers? Surprise surprise, most of them are millennials and high earners. (As an interesting side point, more than 40% of millennials in the United States said they would rather live in a socialist society than a capitalist one.)

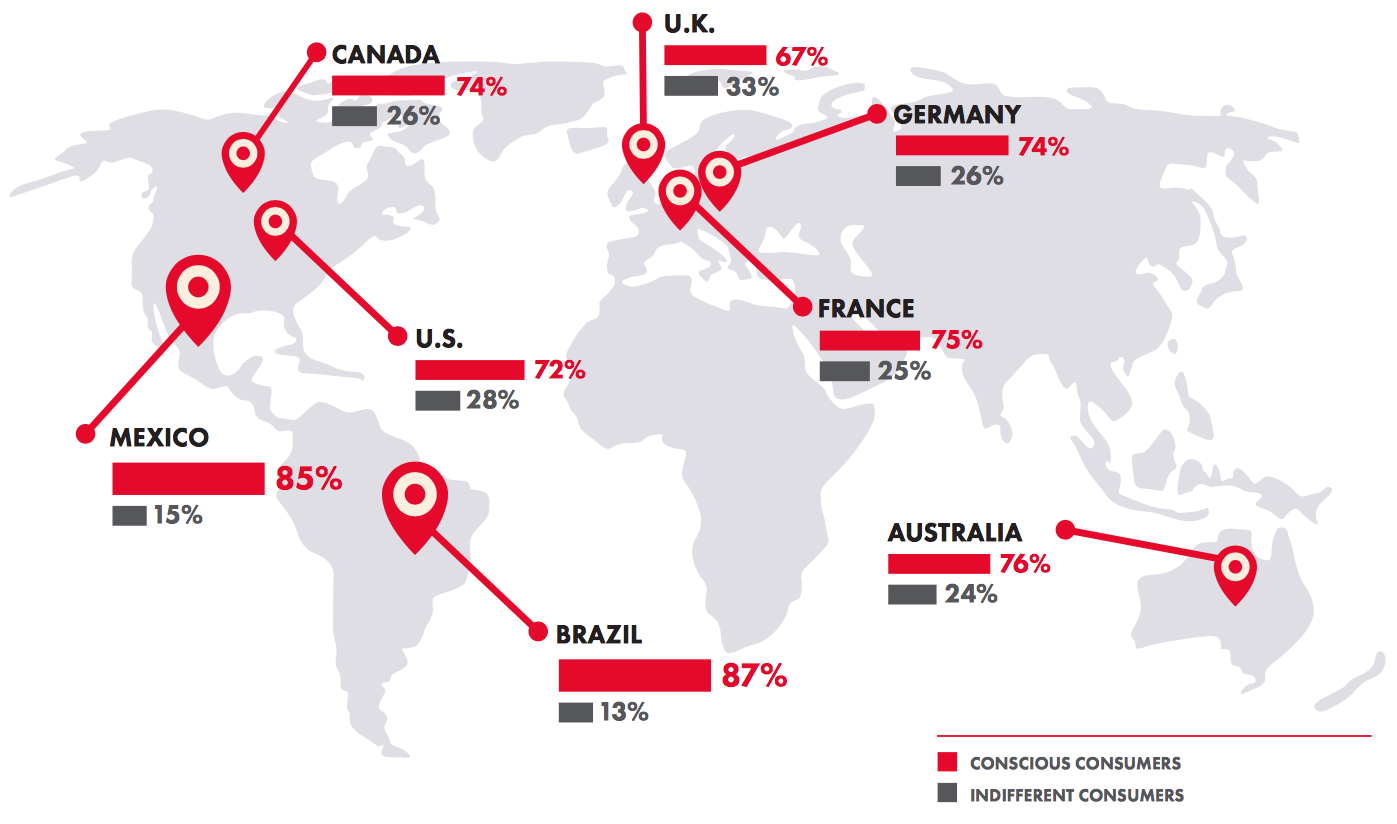

There are plenty of studies and surveys out there documenting consumer trends: health conscious, socially conscious, and environment conscious. For example, the image below shows various proportions of conscious consumers across different countries.

Source: Zendesk

Source: Zendesk

So people buy not just the what (functional benefits) but also the how and the why (emotional, social benefits). Given that millennials consider “self, society and planet,” this extends the “social” aspects of the jobs to be done of a brand.

Movement towards social goodness

Some brands are already taking steps to engage with consumers against the backdrop of falling trust in institutions.

Some get certified as a Benefit Corporation (B Corps), some operate as social enterprises.

Often, these are relatively new companies that are not behemoths in their industries. And they try to assert their unique value proposition through being socially conscious. Here are a few ways to do it.

Using influence to move others

It’s not enough to merely start a conversation. Brands need to invite belief-driven consumers to act and drive the conversation.

Sometimes, a brand’s influence can be indirect. For instance, if you’re doing research for policy makers, you can draw attention to areas that would create a good social outcome. This is the case for a certified B-Corp design company called Today.

I had a chance to speak briefly with the firm’s CEO Damon O’Sullivan. He talked about:

- How their work could directly and indirectly have a social outcome

- Their purpose-driven approach

- The trend of socially conscious brands

You can listen to his comments in the soundbite below.

Being ethical within their own supply chain

As an example, the fashion industry is notoriously bad in this aspect. Thus, startups or smaller fashion brands can tackle the issue and galvanise consumers into buying “slow fashion” instead.

Green Embassy – Australia’s first globally recognised organic fashion label – is a good example. At the aforementioned Future Enterprise event, they showcased the journey of raising awareness, attracting national and global media coverage in the fashion world.

Taking a stance on social issues

Another way of projecting the image of a socially conscious brand is to take a stance. Usually, we see consumer-facing brands at the forefront of this since they’re closer to the public. That doesn’t mean business-facing or B2B brands can’t make an impact.

Source: The Future Enterprise event

Source: The Future Enterprise event

Basecamp – popular project management/team collaboration software – is not shy about sharing their opinions on things like racism or the harmful effects of technology (even though they’re in tech).

And guess what? They just made it to Forbes’ Small Giants list, recognising small companies in the US that “value greatness over growth.”

What about bigger corporate counterparts?

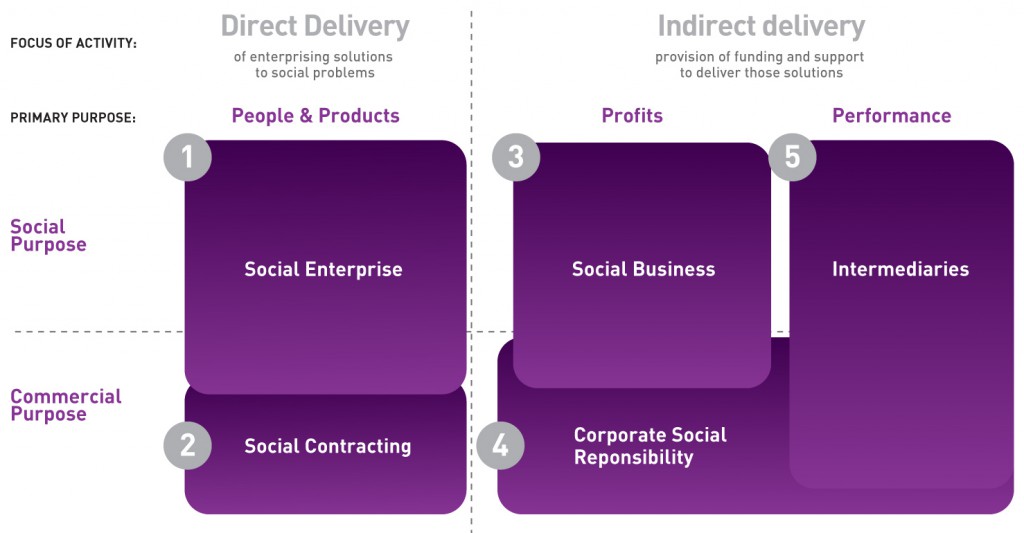

It’s helpful to know where all socially oriented activities fall on the spectrum.

Source: Australian Government

Source: Australian Government

Most corporations’ socially oriented activities would fall under Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) category. These are mostly proactive, periodic initiatives that may have some brand building purposes attached.

Examples: Commonwealth Bank sponsoring Cricket Australia, telco AT&T investing millions in education, The Body Shop partnering with a non-profit for their anti-bullying campaign.

But sometimes they can be firefighting tactics

This means reacting to bad press by launching initiatives that are insignificant compared to the scale of their whole business.

For instance, fashion giant Zara launched their first sustainable collection last year. This could be an attempt to sooth criticism of Zara using cheap labour and ripping off independent designers.

Taking the right social stance yet failing to hit the mark

Sometimes a good idea suffers from poor execution. Take Pepsi vs. Heineken.

On one hand, Pepsi appeared to trivialise political protests by hiring reality TV star Kendall Jenner to “prance around the street carrying a cola.”

Heineken effectively showed Pepsi “how it’s done” with an ad on the same issue not long after that.

Instead of staging the celebrity, police and protestors like Pepsi, Heineken conducted a social experiment that got people talking about their opposing political views over a beer.

Taking the wrong stance or failing to take a stance

After New Balance appeared to support Trump’s trade plans, neo-Nazis tried to co-opt the brand, which fuelled the backlash even more. People filmed themselves burning New Balance sneakers – then dubbed “The Official Shoes of White People.”

Uber also copped the #DeleteUber movement after continuing to operate at JFK airport while taxis were striking against Trump’s travel ban on Muslim-majority countries.

Source: Twitter

Source: Twitter

Doing good and adjusting actions based on feedback

More in the realm of social enterprise is shoe company TOMS. Their “one for one” model started with giving a pair of shoes to someone in need after every customer purchase.

Initially, their giving program attracted some heavy criticism for their ineffectiveness, even saying the brand was merely playing “the fairy godmother.”

The extraordinary thing about TOMS is they actually cared enough to listen and improved their program. This is their current social offering:

Source: TOMS

Source: TOMS

And how are they faring business-wise? Not only is their “buy one give one” model sustainable, they managed to expand globally and attracted investment from Bain Capital – who owns half of TOMS and see their giving and purpose as a competitive advantage.

The cost of inaction or the benefits of action

With potential backlash, it’s not unreasonable for companies to consider the risks. But the rewards are too big to ignore.

Meaningful brands outperformed stock market by 206% over a 10-year period. They also commanded higher pricing and sales.

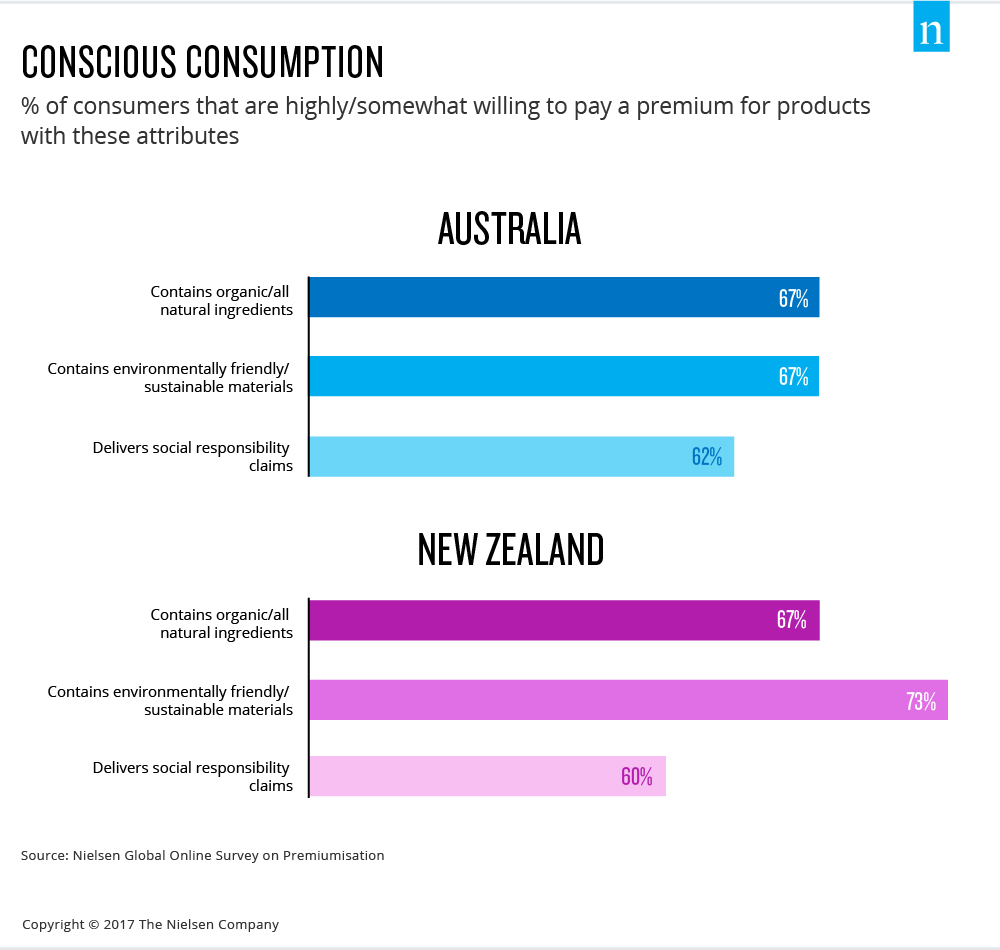

Similarly, 77% of consumers in a multinational survey choose to pay more to purchase from companies demonstrating social responsibility.

The less glamorous grocery sector also has potential in premium pricing if brands can demonstrate social responsibility.

Source: Nielsen

Source: Nielsen

In short, standing up for what’s right is good for business, good for morale, and good for humanity.

What are brands to do?

It’s more than just cause marketing. Or at least it’s going back to basics in cause marketing, which starts by giving from the heart.

Some lessons I took away from the event on how companies can prepare for the future of brands:

Understand your market

Keep track of sentiments around social issues and identify what your target consumers are passionate about.

Stay true to your brand

Pick an issue that’s a natural extension of your brand and try to stay relevant. For example, a beer company advocating against drink driving looks good, but the same company advocating for raising literacy among children may not work as effectively.

Authenticity

Talk less do more. If you want to advocate for gender equality in the workplace and your workforce consists of mainly men, the public wouldn’t be too impressed. Example: Audi’s Super Bowl ad highlighting the issue.

Source: Twitter

Source: Twitter

This quote from Google’s Global Creative Director sums it up nicely:

“It’s a time of brand bravery where brands are really taking a stand, but safe space is disappearing. It’s an easy time for brands to jump onto passions, but what you have to remember is that those passions will define your brand from that point forward. So you have to be able to own it.”

Good examples

Whether you’re an incumbent or startup, there are always opportunities to do good.

Look at ING Dreamstarter initiative, designed to help social entrepreneurs through crowdfunding, scholarships and grants.

We’ve previously talked about pre-commerce and crowdfunding as a potential avenue for product development. Now combine that with social responsibility and ING has created a platform to kickstart social enterprises. The global bank has also generated brand goodwill based on real community impact.

See some stats about the ING Dreamstarter below.

ING also has a host of other initiatives on sustainability, society’s transition, as well as statements (and actions) on issues like climate change.

Now onto a startup example.

Brandless is interestingly, a brand that wants to take on big corporations by selling everyday products without big brands’ price markups. They’re about “inspiring a new wave of consumer culture that makes sense, created in direct opposition to a system that isn’t serving people.”

Everything sells for $3 each. Source: Brandless

Everything sells for $3 each. Source: Brandless

Not quite on the same scale as Toms shoes’ “One for one” business model, Brandless also gives part of its sales back to the community.

Concluding words

Is it a case of “With great power comes great responsibility?” Or as long as we “disrupt” a market, make a billion-dollar exit, no one would question if we’re a socially conscious brand?

Consumers are becoming more demanding and vigilant, particularly in these divisive socio-political climates.

Brands need to speak about doing good as well as doing it. Or consumers won’t buy it, literally.

Continue the conversation by tweeting to us @EnabledHQ